Venusian Atmospheric Probe Explorer

Project Status: 90%

Introduction

Oh yes, that name is definitely intentional. Well this has everything to do with clouds, except there made out of poisonous sulfuric acid. This is my “simple engineering approach” research into what a low cost, sustained Venusian Atmospheric Probe Explorer (VAPE) might look like.

So after building model rockets, high altitude balloons, quadcopters, robots, etc, I decided I purse a much bigger concept I’ve been thinking about a lot. Despite the fact that Mars has been the focus of most of humanities exploration goals, Venus has some amazing longer term qualities that really fascinate me. If I just showed you a table, you might even scratch your head on the Mars missions.

| Property | Venus | Earth | Mars | Moon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gravitational Force (m/s2) | 8.87 | 9.81 | 3.71 | 1.62 |

| Solar Energy (Watts/m2) | 2613 | 1368 | 590 | 1368 |

| Travel Time (Earth Days) | 145.964 | - | 258.676 | ~3 |

| Velocity for Hohmann Orbit From Earth Orbit (km/s) | 2.5 | - | 2.9 | - |

| Time Between Launch Windows (Earth Years) | 1.599 | - | 2.135 | - |

| Year Length (Earth Days) | 224.7 | 365 | 687 | - |

| Average Distance from Earth (AU) | 1.135 | - | 1.693 | 0.00257 |

| Average Round Trip Comm Time | 18.3 min | - | 28.2 min | 2.6 sec |

*Data is likely debatable but horizontal rows are source congruent for comparison

Distance Calculations

I’m a bit of a believer in “closer is better” when it comes to space, and since this is a small step in the long term mission towards human inhabitation of other celestial bodies, I decided to do the math out and see what communication times are going to be like. First, I used a simplified formula for finding the average distance between roughly spherical orbiting bodies over an infinite span. From there it is simple unit conversion to see how long the round radio talk time is. This source was particularly helpful in the distance calculations and there accompanying video is a cool demonstration of why Mercury is actually the closest planet to Earth. Anyway, the output shown below is also in the above table.

pip install scipy

import math

from scipy import special

from scipy import constants

# Constants

auToMeters = 149597870700 # ~150 million kilometers

earthMoonDist = 385000600 # Earth to Moon in meters

earthAU = 1 # distance from Earth to Sun in AU

venusAU = 0.722

marsAU = 1.524

# Average distance between two approximately circularly orbiting objects

def averageDistance(r1, r2):

x = (2 * math.sqrt(r1*r2)) / (r1 + r2)

return (2 / math.pi) * (r1 + r2) * special.ellipe(x**2)

# Average time for round trip signal at speed of light

def averageRoundTripTime(dist):

metersDist = dist * auToMeters

travelTime = metersDist / constants.speed_of_light

return 2 * travelTime

# Earth - Venus

earthVenusDist = averageDistance(earthAU, venusAU)

earthVenusTime = averageRoundTripTime(earthVenusDist)

print("Average Earth to Venus Distance: %0.3f AU" % earthVenusDist)

print("Average Earth to Venus Round Trip Time: %d seconds\n" % earthVenusTime)

# Earth - Mars

earthMarsDist = averageDistance(earthAU, marsAU)

earthMarsTime = averageRoundTripTime(earthMarsDist)

print("Average Earth to Mars Distance: %0.3f AU" % earthMarsDist)

print("Average Earth to Mars Round Trip Time: %d seconds\n" % earthMarsTime)

# Earth - Moon

earthMoonDist = float(earthMoonDist) / auToMeters

earthMoonTime = averageRoundTripTime(earthMoonDist)

print("Average Earth to Moon Distance: %0.9f AU" % earthMoonDist)

print("Average Earth to Moon Round Trip Time: %0.3f seconds" % earthMoonTime)

Output

Average Earth to Venus Distance: 1.135 AU

Average Earth to Venus Round Trip Time: 1133 seconds

Average Earth to Mars Distance: 1.693 AU

Average Earth to Mars Round Trip Time: 1689 seconds

Average Earth to Moon Distance: 0.002573570 AU

Average Earth to Moon Round Trip Time: 2.568 seconds

Solar Energy Analysis

Just a quick foray into Space Engine demonstrates how different the amount of light each planet receives. In terms of humans, more sunlight equals more energy. You can clearly see Venus gets about twice as much sunlight as the Martians, and no this isn’t playing with angles; probes sent to Mars have 4 times more solar panels (inverse square law for light).

Venus

Mars

Composition

Surface composition is very similar across the three major terrestrial planets. At the surface of Venus, the material composition isn’t entirely disimilar to Earth from what we can predict scientifically during our solar systems planetary formation as well as what we know from the Soviet landers.

The Harsh Reality

Unfortunatly, there is a simple rational argument for Mars as the target for planetary expansion: Venus is a living hell at the moment. With surface temperatures exceeding 800* Celcius and pressure exceeding 92 Earth Atmospheres, humans walking on our sister planet just isn’t happening anytime soon. Furthermore, terraforming is difficult as bio-structures heavily rely on hydrogen which Venus has all but depleted. Without a magnetic field to protect from solar winds, the hydrogen has slowly “leaked” off the upper atmosphere.

| Property | Venus | Earth | Mars | Moon |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siddereal Day Length | 243.025 days | 24 hours | 25 hours | 28 days |

| Solar Day Length | 116.75 days | 24 hours | 25 hours | 28 days |

| Average Surface Temperature (°Celcius) | 462 | 14 | -63 | 107 / -153 |

| Surface Atmospheric Pressure (atm) | 93 | 1 | 0.006 | 0 |

| Surface Magnetic Field (gauss) | None | 25 - 65 | None | None |

The Big Idea

My idea is to take advantage of uniquely Earth-like atmospheric conditions to put a scientific probe into the upper atmosphere. My rational is an extremely low cost probe would have minimal risk compared to a larger, more expensive payload, and would teach us enormous amounts about how the Venusian climate functions. Everything from the wind current forces, Soviet “rain” conjecture, sustainability of solar visibility for the solar panels, and longevity of an atmospheric spacecraft could be tested without much fear of losing the craft.

In a list my major goals are as follows:

- ultra low cost

- open source

- design

- hardware (electronics)

- software (CFE or fPrime, not sure which framework yet)

- launchable on low cost rocket (ideally cheap launch cost but lowers dimension capability)

- design to remain afloat for as long as possible in atmosphere (a la Oppurtunity on Mars…)

- buildable (I would like to build it, not sure why)

Background Research

It wouldn’t problem solving if I didn’t start with researching what we do and do not already know. The two major operational Venusian missions to analyze are the HAVOC (High Altitude Venus Operational Concept) created by NASA and the balloons flown on Venus by the Soviets during the space race.

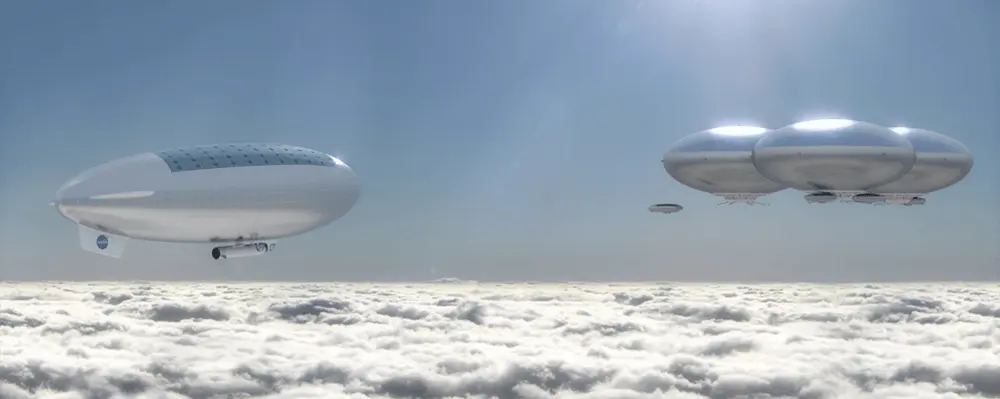

HAVOC

NASA Goddard’s proposal involves a two phase approach. First, a steerable robotic blimp makes its way to the Venusian atmosphere with a largely scientific payload to study the environmental conditions and prepare for the next phase which is sending humans in a much larger blimp. From here, the decision on colonization of our sister planet can be thoroughly evaluated.

Its an awesome proposal, all credit to the mission concept team at Goddard. From the outside, it seems to cover everything my probe does and more and to be honest when I started reading the extensive research documentation, I nearly axed this project. So what am I doing differently? Dirt cheap cost, minimal risk, and simple design for easy iteration. I actually consider my concept to be a further precursor to robotic mission of the HAVOC. Losing a tiny blimp due to some unforseen conditions is far easier on the taxpayers than a 100+ foot long blimp. Plus, worst case, you realize it isn’t good enough for further mission planning, you can just gather up the images and science data and save yourself the trouble until bio-technology advances to where you can terraform the planet.

Soviet Balloons

A sleeper in the space race, the Soviet exploration of Venus is mind numbingly interesting. As part of their Venusian lander program, they also sent two balloons into the upper atmosphere, albeit without any kind of energy generation so they only lasted a day or so. Still, they provide a great starting point for developing my small scale blimp concept and give detailed measurements on wind forces, suggests of “rain” as they slowly sunk, and a comparable model for buoyancy forces.

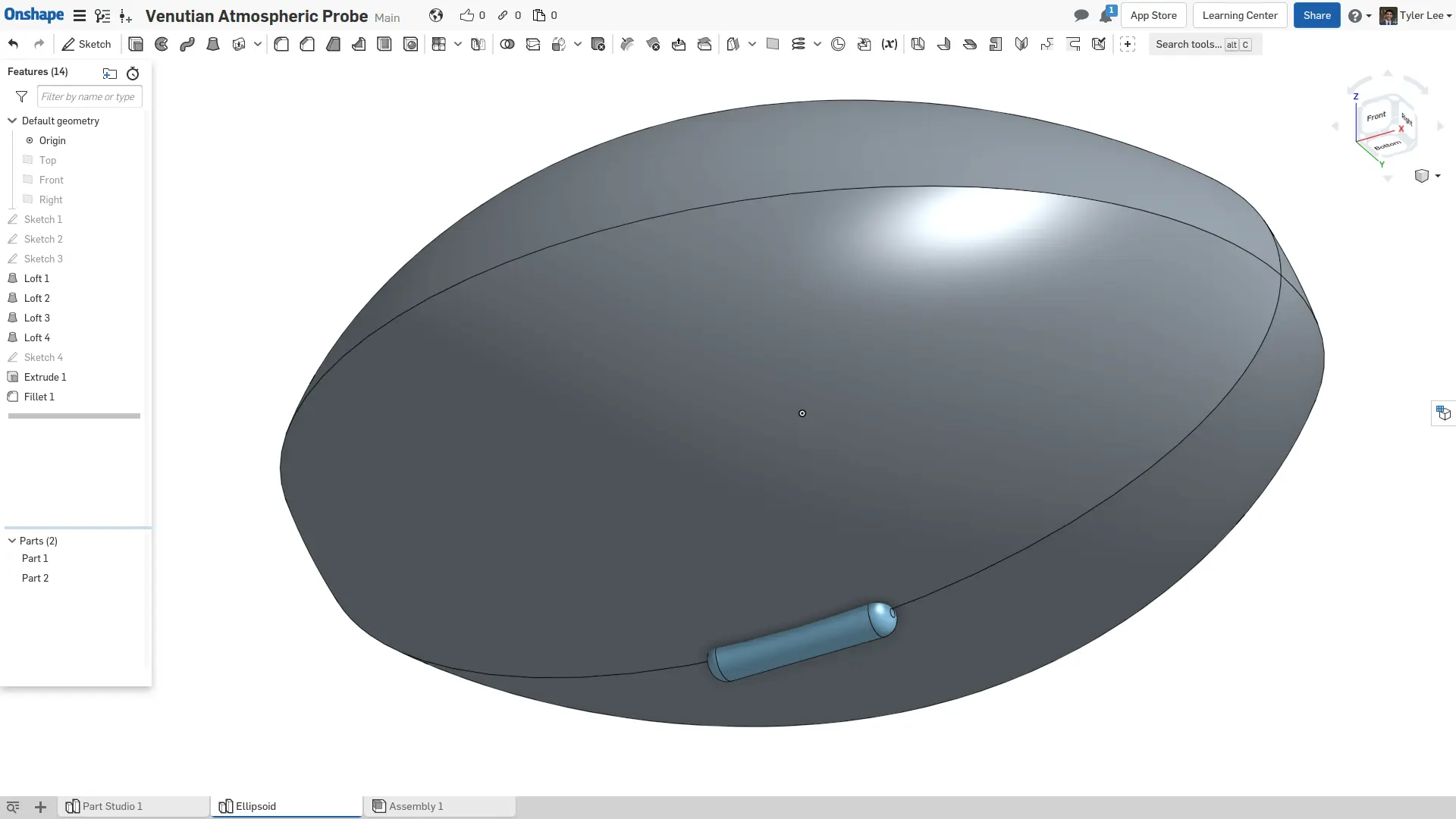

Concept

So based on the Soviet balloon payloads, I wanted to create a target model with similar bouyancy characteristics, meaning a similar volume. I also wanted to incorporate a mildly flat surface for solar panels so I decided on an elipsoid. Messing around with a few axial parameters in vPython I came up with the following as a satisfactory model.

pip3 install vpython

from vpython import *

import math

scene.width = 1920

scene.height = 1080

### Soviet Balloons

volume = 4/3 * math.pi * (1.75 ** 3)

sphere(pos=vector(-10, 0, 0), radius=1.75, color=color.red)

label(pos=vector(-10, 4, 0), text="Soviet Balloon\nVolume: %0.3f" % volume)

### 25 kg sphere

radius = 1.814

volume = 4/3 * math.pi * (radius ** 3)

sphere(pos=vector(-5, 0, 0), radius=radius)

label(pos=vector(-5, -3, 0), text="25 kg Sphere\nVolume: %0.3f" % volume)

### 25 kg ellipsoid

length = 5.305

width = 4

height = 2.5

volume = 4/3 * math.pi * (length/2) * (width/2) * (height/2)

ellipsoid(pos=vector(0, 0, 0), length=length, height=height, width=width, color=color.blue, axis=vector(0, 0, 1))

label(pos=vector(0, 4, 0), text="25 kg Ellipsoid Front\nVolume: %0.3f" % volume)

ellipsoid(pos=vector(5, 0, 0), length=length, height=height, width=width, color=color.blue, axis=vector(1, 0, 0))

label(pos=vector(5, -3, 0), text="25 kg Ellipsoid Side")

ellipsoid(pos=vector(10, 0, 0), length=length, height=height, width=width, color=color.blue, axis=vector(0, 1, 0))

label(pos=vector(10, 4, 0), text="25 kg Ellipsoid Top")

Interactive Output (right click and drag to move on desktop)

Design

Once I had my shape, I used my favorite CAD tool to make a quick rendition of the ellipsoid design, with a few changes. First, CADing an ellipse is a pain, so it isn’t the perfectly round shape I hoped for. Second, I added a tubular payload to the bottom of 1 meter in length, and 15 cm in width to support a “cubesat” like payload which I’ll get to later. Ideally, this will be easy to attach to the bottom of the blimp and not provide much drag for the hurricane strength winds of Venus. Winds which lead me perfectly to the next part: Computational Fluid Dynamics.

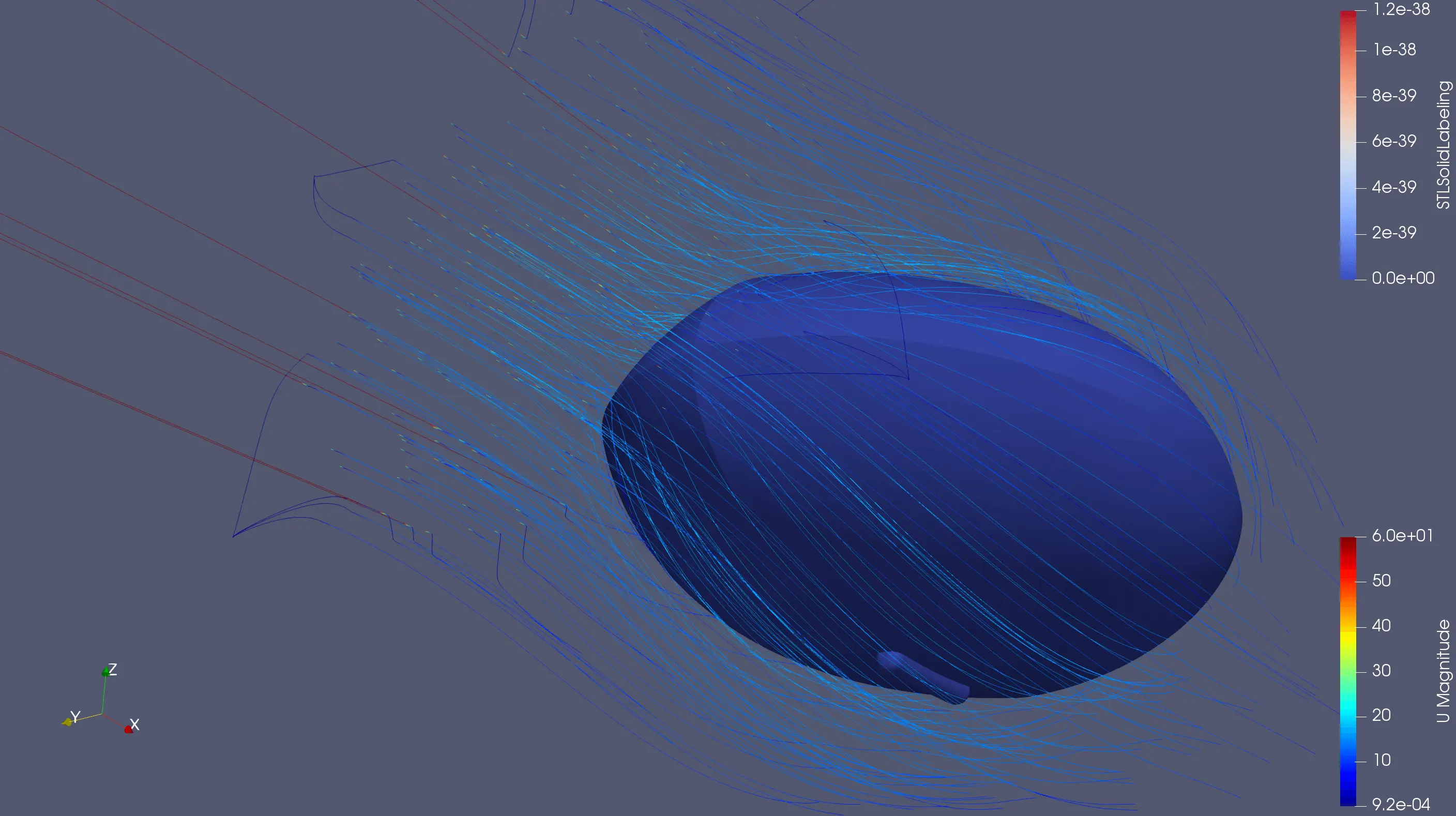

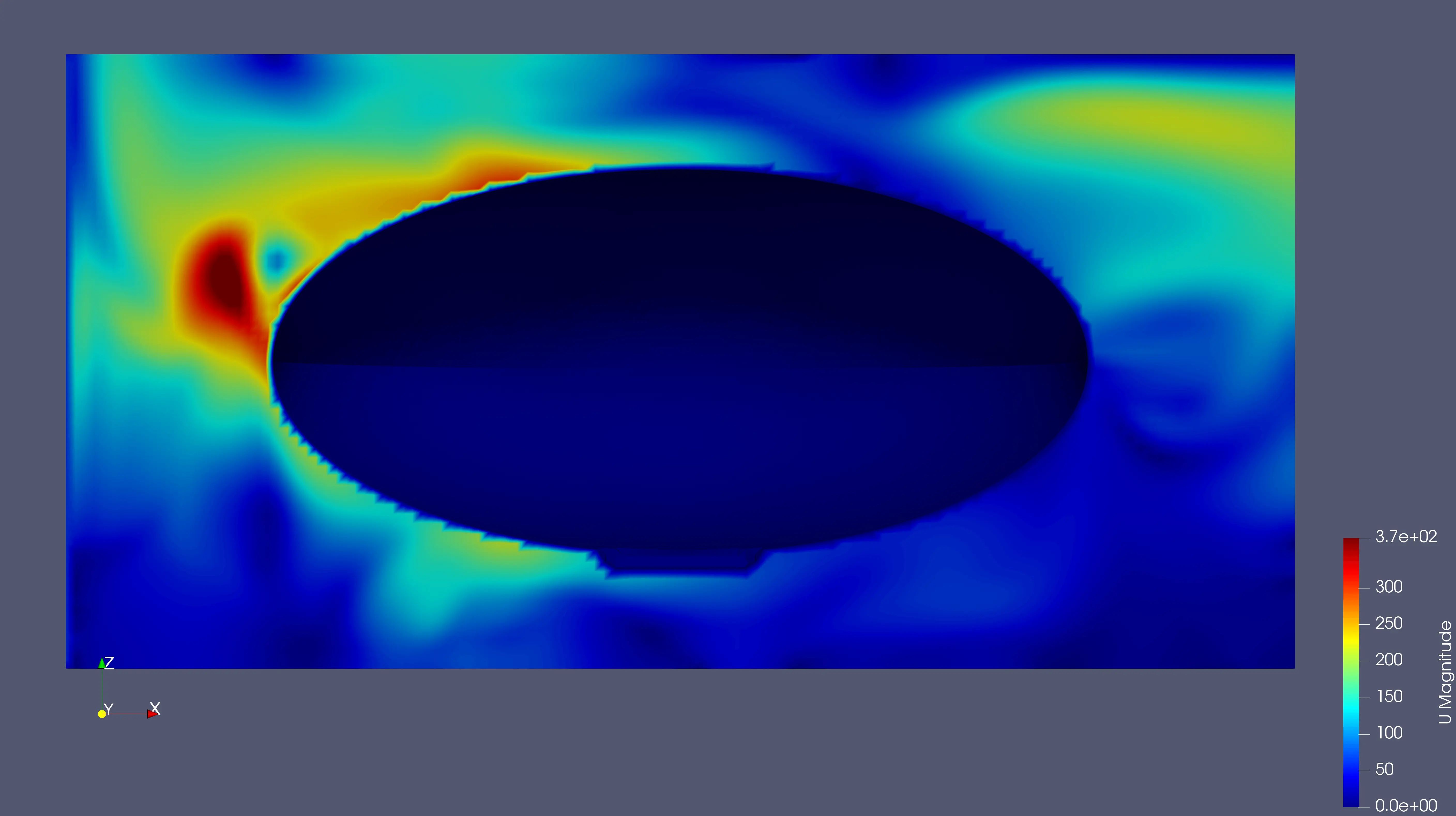

CFD

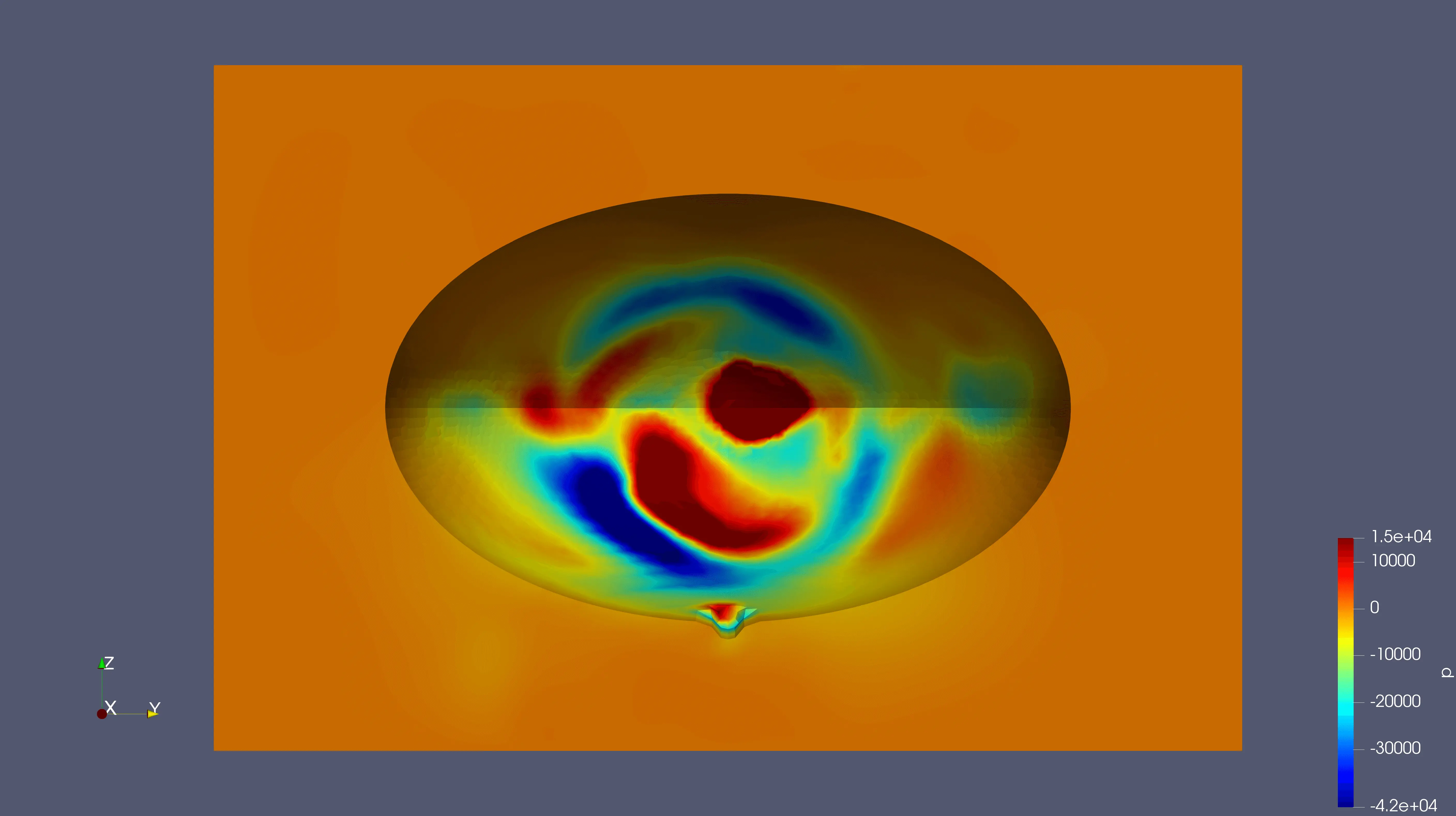

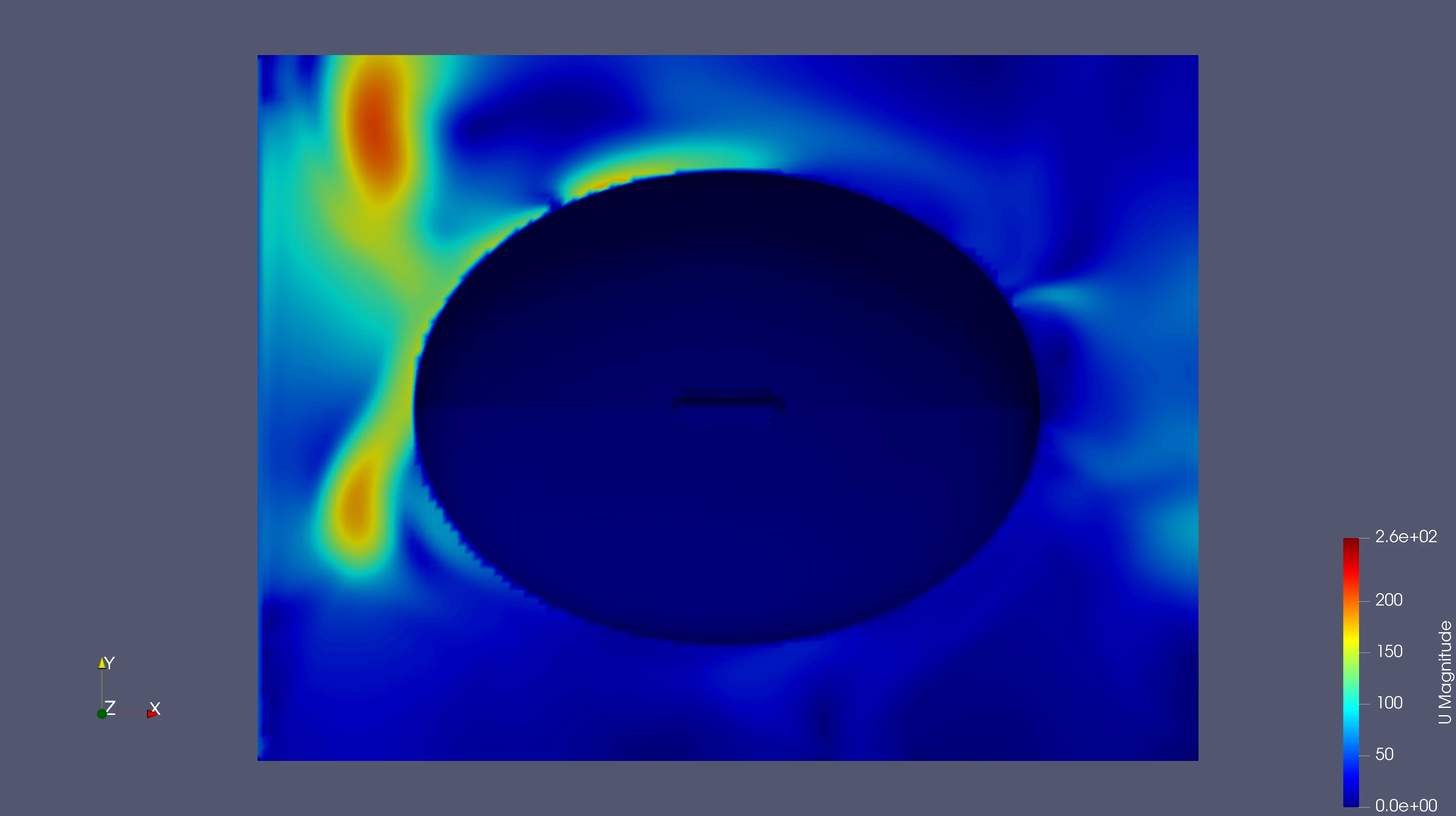

I had never used computational fluid dynamics before so step 1 was learn CFD. A week of low definition Russian and German videos and a lot of software exploration later, I settled on a Heylx OS frontend, Openfoam backend with Paraview for visualization. One of these days I’ll get around to making an English version of analyzing external flows on an STL model.

As an astute colleague pointed out, I really don’t have a baseline to compare my models to, but as a CFD novice, I’m fairly certain they aren’t the most accurate thing anyway. However, they certainly look pretty and made my server scream. I was mainly trying to figure out if my payload tube would generate massive interference and how well the “edge” (middle section from the side) of the blimp would fair in gale force winds. Predictably, there is clearly some strong forces involved but I don’t think it would be the end of the world for the blimp.

Stream Trace

Side View of velocity shows current predictably moves faster on top due to shorter path - bernoulli effect

Forward facing mid-section cut of pressure showing high pressure on the nose and tubular payload.

Top down view to mid-section cut of velocity shows some drag and current around “edge”

Software

Between hardware and software, this is the easy one, so I’ll start with it. In following with my belief of open source being better for the world with lower barriers to entry as well as being more easily scientifically replicated, its basically down to NASA JSC’s fPrime and NASA Goddard’s Core Flight Executive. I personally prefer the slightly more modern and intuitive fPrime so thats probably what it will be, albeit with a reworked front end.

Hardware

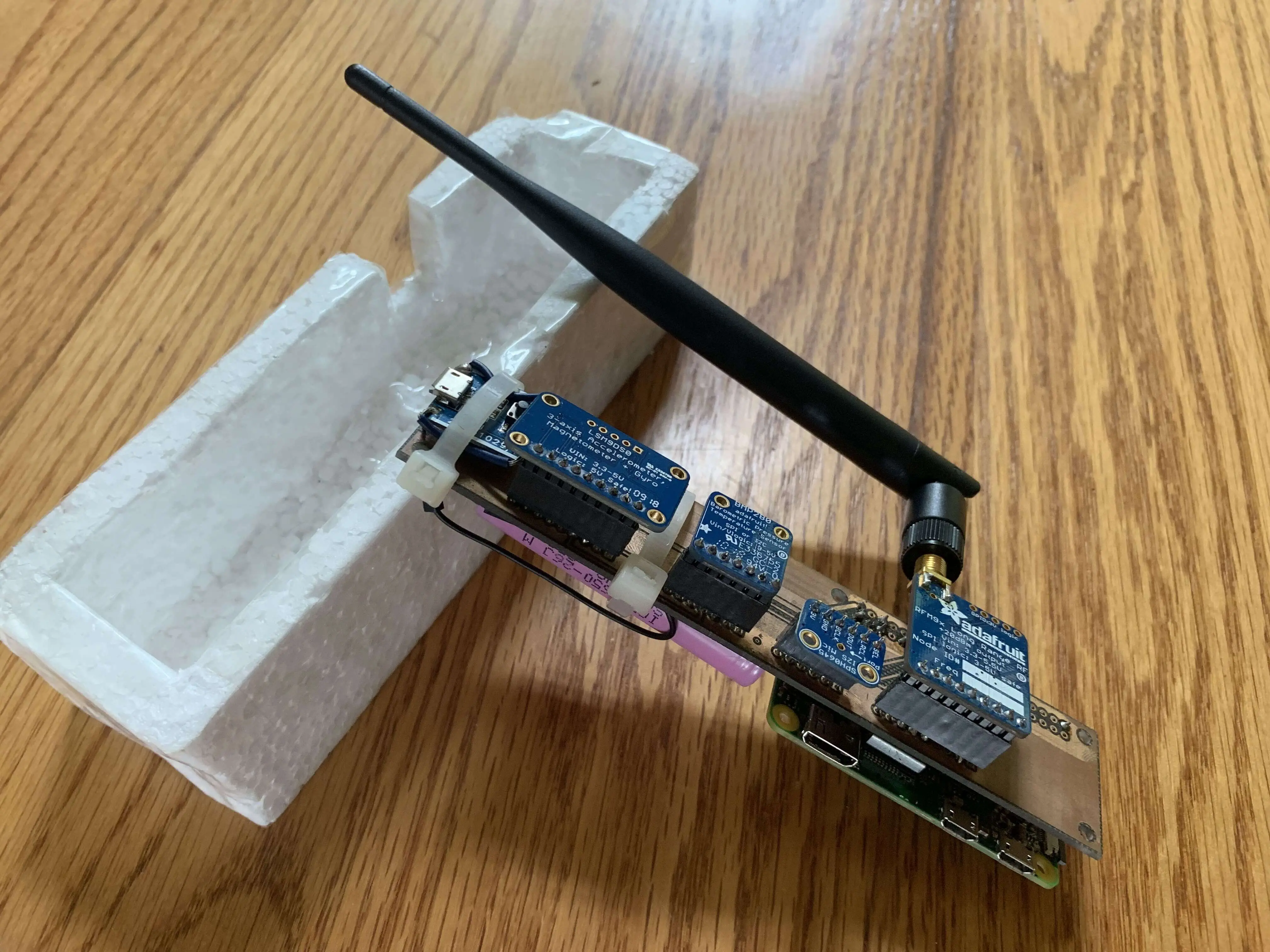

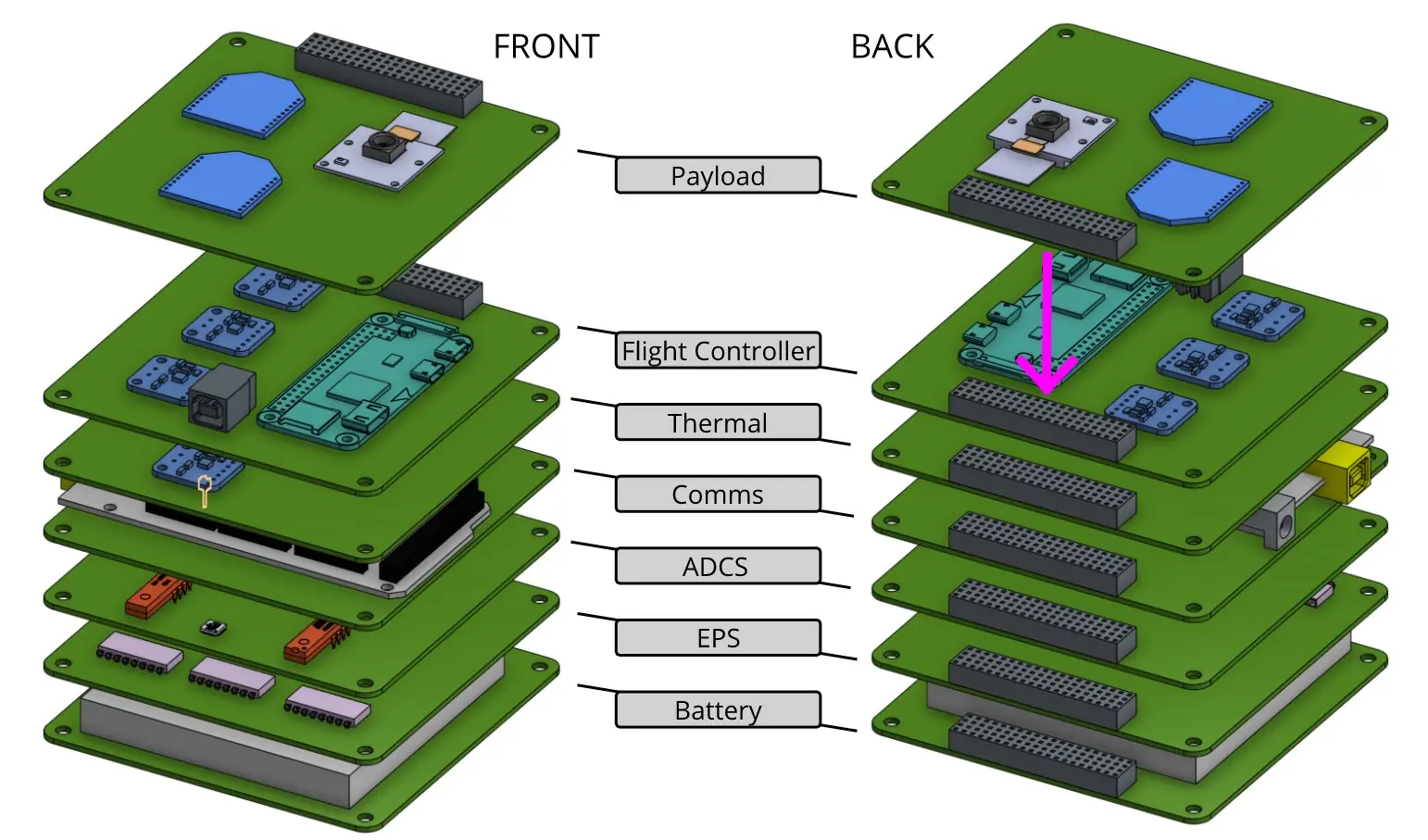

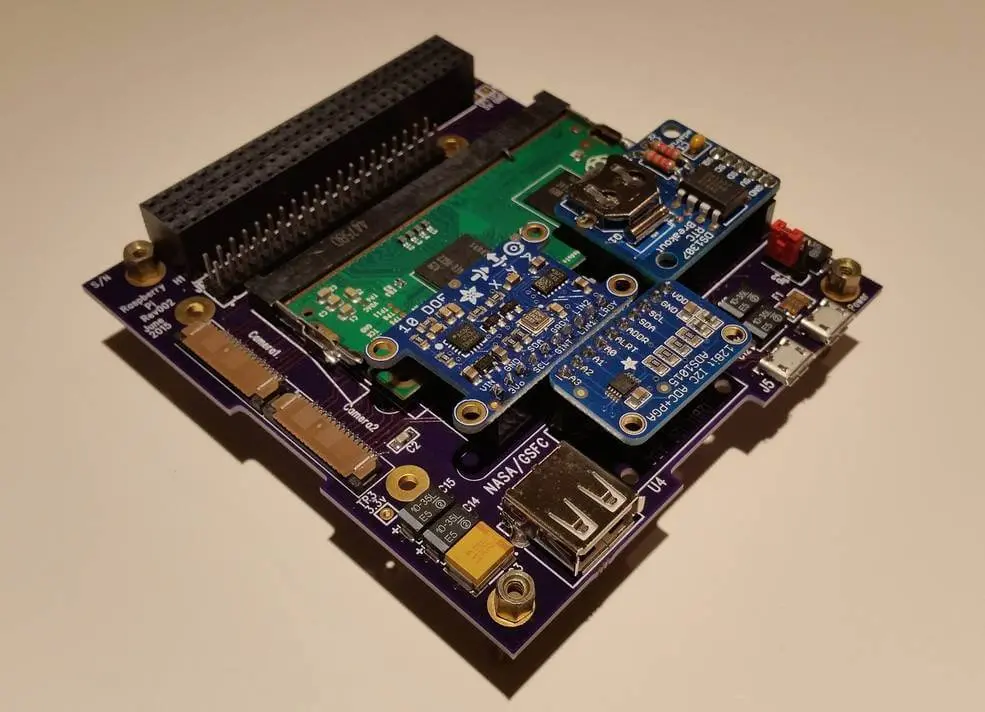

This is the fun part, I really believe in lowering barriers to entry and while there are some open source satellite concepts out there, they just aren’t robust enough in my opinion. From a prevous project on a Raspberry Pi powered rocket core I belive there is a niche for a hyper low cost cubesat hardware/software framework. I started developing a model until I found Goddard’s b-e-a-u-tiful Pi Sat Concept. It incorporates so many wonderful ideas: modular design, easy upgradability, wide spread knowlegde of how to program with a plethora of resources - I dare say it is exactly what I was hoping to build. Of course, for the Venusian probe it will definitely have to be tested in rugged conditions and healthly flattened down a soldered package.

Rocket Core, as configured for high alitutde balloon flight

Early Flight Stack Concept, using a pi zero for processing

Goddard’s Pi Satellite “Dev Kit” using a Pi Compute Module, Rasbperry Pi 40 pin header, and a fairly standard satellite PC 104 stackable bus

Conclusion

It is a fun project with a lot more to add/learn/work on. I don’t really intend for their to be any substantial outcome, it was just a fun excercise in “what if” that happens to be incredibly illuminating to me. If I were to develop a conclusion, well, Venusian colonization is a few major technological leaps away and we should really focus on the moon. And so begins my next project, a low cost lunar science lab…

Links to Add / Sources

Venusian Conditions

- Forbes Mars vs Venus

- Gas Resistivity

- Atmosphere Radiation

- Blimp Aerodynamics

- Megellan NASA

- Densities/Temperatures Venusian Atmosphere

- Co2 Deep Atmosphere

- Low Altitude Exploration of Venus Atmosphere

- Venus HAVOC Hype Video

- Clouds of Venus Dyamics Uncertainty

- HAVOC Concept NASA

- https://ntrs.nasa.gov/search.jsp?R=20160006329

- Colonizing Venus

- European Venus Explorer Concept

- Russian Balloon Calcs

- Depth Pressure Calculator

- Venus Weather Patterns

- Mars Composition

- Hohmann Transfer window speed up

- Earth to Venus time

- Venus Closest Neighbor

- Terraforming Venus/Mars

- Venusian Atmosphere

- Venus Winds

- Venus Rain

Satellite Hardware

- Arduino Power Consumption

- Raspberry Pi Power Consumption

- Batteries

- Pumpkin Battery

- https://www.pumpkinspace.com/store/p198/Intelligent_Protected_Lithium_Battery_Module_with_SoC_Reporting_%28BM_2%29.html

- NASA GEVS

- Pi Sat

- RC Model